An Interview by Jennifer Konieczny

An Interview by Jennifer Konieczny

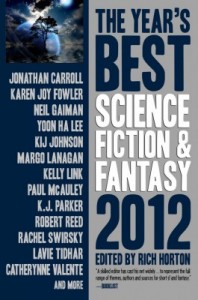

“Canterbury Hollow” by Chris Lawson will be appearing in Prime’s forthcoming Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy: 2012 edited by Rich Horton. Pre-order here!

In your January 2011 interview with Fantasy & Science Fiction, you said “Canterbury Hollow” was inspired by Proximity Zero by Terry Kepner, “a catalogue of near-Earth stars for role-players.” How often do you find inspiration from reference materials? Could you tell us about your usual writing process?

Most of my ideas come from non-fiction, from a range of sources that includes reference books. I bought Proximity Zero because I wanted to know which local stars were relatively sun-like and how an interstellar civilization might evolve outwards from our solar system. Discovering that Gamma Leporis was reported as having different colors by different historical observers was a completely unexpected find from my reading. Years later, that recollection fused with another story idea about a doomed colony and became “Canterbury Hollow.”

I’m not sure I can apply the word “process” to my writing; that’s giving me far too much credit. Every story comes from a different place. For me, a scientific or thematic idea is almost always the seed and then slowly the characters and the story coalesce around the idea (and sometimes they derail the first idea for a better one). I used to take notes about story ideas, but now I prefer to let them simmer and if I forget an idea, I assume it wasn’t strong enough to be worth writing up. The only notes I keep are for specific details and references that I need to get right when it comes time to write the story.

Your short story, “Canterbury Hollow,” has been described as “science fiction with a very human touch.” How do you balance the two when writing?

A scientific idea can’t become a story until it affects at least one person (well, one plausible character); ideally, the person should have some influence over what is happening to them, even if that influence is minor. If the story is just an idea by itself, then that idea had better be pretty damn fascinating. When the story is about a choice that a person makes in the face of an idea, and the choice is important to that person, then the writer has a good framework.

How does your work as a family physician impact your writing?

For one thing, I’m much more familiar with biomedicine than other branches of science. Some of the stories I’ve written would never have occurred to me if I had no background in medicine. At least two of my stories were triggered by reading specific papers and wanting to explore the ideas raised (“Screening Test” and “Empathy” if anyone’s interested).

What a career in medicine gives a writer is an understanding of how people react to major life events. Not only have I seen people deal with terrible situations, I’ve seen lots of people do so with a wide range of responses. Much of the daily work of medicine is as mundane as any other job, of course. I have yet to see a trolley burst through the doors of an Emergency Department with a phalanx of people in blue scrubs yelling “STAT!”, although according to television it’s an hourly event. The real drama in medicine is slow, unfolding over months or years.

You said, in the same interview, that you are “fascinated by the human need to find meaning in everything.” Why do you think we are driven to find meaning?

That’s a big question for a mini-interview!

My (probably unpopular) back-of-the-envelope answer is that as we evolved, our bodies have given more and more control over decision-making to our nervous system, because our nerves are able to react faster to complex situations than our cellular biochemistry can. In order to keep our nervous system from making decisions contrary to our biological needs, we have built-in goals like “drink enough water to survive” and “find shelter from damaging agents.” These basic purposes are still overlaid on the biological needs — feelings like thirst and pain are direct neurochemical punishments to keep our brains in line, and there are neurochemical rewards as well.

Over evolutionary time, we developed the capacity for more abstract purposes like drawing a beautiful picture or figuring out how to make a steam engine (the first was a toy from ancient Greece, not an industrial device). Some of this no doubt ties in with our basic needs, like brolgas dancing as part of their mating decisions, but some of it has no obvious biological advantage and sometimes even a distinct disadvantage.

Our cognitive abilities have outgrown our basic biological needs and we find ourselves pining for ways of living that will give us the same sense of satisfaction that we can meet on the biological level by having a good meal or good sex—except that we want the satisfaction to be less ephemeral. There is no such thing, of course, but we keep on looking for this magical purpose and find it in all sorts of places, sometimes admirable and sometimes not, and we often project our personal desires onto external, often imaginary agents because we don’t like to acknowledge how capricious our sense of purpose can be.

And that’s the short version.

If you had a known amount of time left—to borrow Arlyana’s question—what would you want to do with your time?

Because I’m at a different stage of my life to Arlyana and Moko, I’d choose to write some novels and see my children safely into adulthood. If there wasn’t time for either of those, I’d like to go into orbit, or as a more realistic alternative, at least take a parabolic flight.