An Interview by Gina Guadagnino

An Interview by Gina Guadagnino

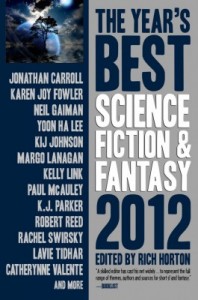

“Cartographer Wasps and Anarchist Bees” by E. Lily Yu will be appearing in Prime’s forthcoming Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy: 2012 edited by Rich Horton. Pre-order here!

The careful structures of the wasp and bee societies are integral to this story. Can you tell us if it was those structures that inspired the story, or if they happened to fit the story you wanted to tell?

I must have been aware on some level of that long tradition of writers and scientists, Virgil to Bernard Mandeville to James Gould, fascinated by the parallels between eusocial insects in general and bees in particular—the hive, the swarm, the nest—and human political realities. Maurice Maeterlinck wrote a beautiful little book called The Life of the Bee, which I first stumbled on in epitaphs to Laurie R. King’s The Beekeeper’s Apprentice many years ago, and bought; it is a short series of meditations and observations on the beehive and its inhabitants that frequently take flight into philosophical wonder. He writes of the swarm:

Where is the fatality here, save in the love of the race of today for the race of tomorrow? This fatality exists in the human species also, but its extent and power seem infinitely less. Among men it never gives rise to sacrifices as great, as unanimous, or as complete. What farseeing fatality, taking the place of this one, do we ourselves obey? We know not; as we know not the being who watches us as we watch the bees.

I had studied some entomology in high school; then in my sophomore year at Princeton a beekeeping club was formed, and I began attending classes and hanging around the hives. (We just caught a small swarm on campus last Wednesday.) Somehow all of these things combined with a graduate course on postcolonialism and the deadline for the Dell Awards to make a whole story.

These are guesses. I’m waffling. There are some stories that come to you by grace, or by a neutrino hitting your brain, whose origins are unfathomable. This was one of them.

The story unfolds along two timelines: the human timeline of a few short seasons, and the insect timeline of generations and regime changes. What was it like to write along two such disparate timelines and keep both in focus?

The humans arrived in a later revision. The first version of the story, which I wrote in December and sent to the Dell, had only the basic drama of the insects. In February or March I revised it to include the story of the people who affected and were affected by the two small societies, playing off Maeterlinck’s idea of our own “spiral of light” being like that of the bees, vulnerable to unknowable forces that might bring sudden, transcendent meaning to our lives, or destroy everything. For this I had to fit together the lifespan of the average worker bee, that of the average queen, and that of the average Japanese wasp, and the Chinese academic year, much like little pieces of a mosaic, then count the months that passed.