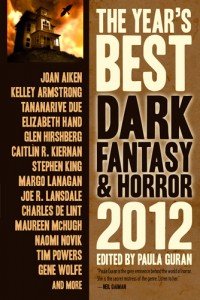

“Catastrophic Disruption of the Head” by Margo Lanagan will be appearing in Prime’s forthcoming Year’s Best Dark Fantasy & Horror: 2012 edited by Paula Guran. Pre-order here!

What was it about this particular fairytale that drew you to retell it?

The dogs with the giant eyes, definitely; they were about the only things I remembered from hearing the story in my childhood, and they were powerfully frightening when I was small—wasn’t much of a dog person then.

Also, the tinderbox itself; there’s always some interesting object in a story that invites my fiddling fingers. What do tinderboxes look like, and what’s in them? Well, more than I thought, it turns out. I found out quite a lot about tinderboxes, before I decided to modernize the tinderbox into a Bic cigarette lighter.

Then when I went researching the story for the purposes of rewriting it, I found it to be fairly morally bankrupt, and I thought that there was a mission laid out for me, to teach that soldier a lesson—or at least give him the opportunity to learn one, which he doesn’t get in the Andersen story. And I was off.

In your version, the soldier veers back and forth from being brutally violent to almost naive and desperate for love. What was it like to write those two opposing sides of his personality?

Well, neither version of him is terrifically intelligent or self-aware, and his veering is part of his lack of reflection. He doesn’t have an awful lot of control over himself; he just reacts to whatever circumstances present to him, from his gut and from what childhood lessons he’s remembered. In a way that makes him easier and more colorful to write: put an irritant in front of him and off goes his temper or his terror, so he shoots someone or destroys something, or takes a lot of drugs to avoid what he’s seeing; put a woman in front of him and he’s torn in four by mixed lust and scorn and mother-love and fear of the unknown.

Quite a lot of the story is simply presenting this veering, without him realizing how horrendous he’s being or how pathetic; it’s only at the end that he begins to feel a faint whisper of developing conscience, a realization that things don’t have to be this way. So it was exhausting, primarily. I could only watch this fellow for so long, and I was glad of any pause I got between drafts, and it was always a matter of taking a deep breath and steeling myself before plunging in again. There was very little compensatory beauty or sweetness in this story; it was a relief to be done with it, I have to say.