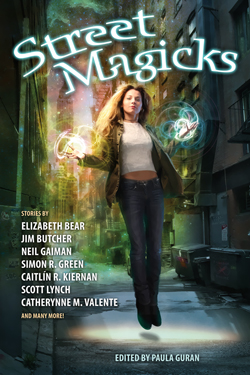

Introduction: Practices and Paved Paths

Paula Guran

“The magic of the street is the mingling of the errand and the epiphany.” —Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking

Magicks? Just a way to convey the stories collected herein all feature some variety of magic. Not just an overall atmosphere of the supernatural or the paranormal, but an act or example of the existence of “real” magic in the world of the author’s making.

As for street…

A street is, generally, a public thoroughfare (usually paved) with buildings on one or both sides of it. It might be a road, but roads exist for transportation and aren’t defined by the edifices lining them. A street does more than provide a path: it is a shared space that facilitates social interaction. Streets are urban. “The street” also means the people who live, work, and gather in streets: the common people who are a repository of public attitudes, knowledge, and opinion.

A street is, generally, a public thoroughfare (usually paved) with buildings on one or both sides of it. It might be a road, but roads exist for transportation and aren’t defined by the edifices lining them. A street does more than provide a path: it is a shared space that facilitates social interaction. Streets are urban. “The street” also means the people who live, work, and gather in streets: the common people who are a repository of public attitudes, knowledge, and opinion.

Streets are places of celebration. We still honor our heroes and celebrate holidays with street parades. Religious processions are not as common as they once were, but many still exist. (And though it is often forgotten, Mardi Gras and Carnival are religious celebrations taken to the streets.) We still have funeral processions as well as street fairs and festivals.

These and other communal outpourings have long served to relieve the tensions of the people dwelling closely together and city life.

Until the early nineteenth century, streets were the primary stages available for music, drama, puppet shows, jugglers, and all forms of common entertainment. And, since the sixteenth century, streetwalker has meant a prostitute who solicits on the pavement.

Street peddlers were once common. Since they conducted business without stationary shops, mobility meant one’s wares might include the less than legally acceptable or material of interest only to the lower echelons of society. Popular media like the penny dreadfuls and Bibliothèque bleue could be easily distributed by street hawkers, as could seditious and inflammatory pamphlets.

Town criers and bellman (so-called because they rang a hand bell to gain attention) once walked the streets as the only means of conveying legal proclamations, bylaws, and notices of market and other special days to mostly illiterate urban dwellers.

Even after the masses learned to read, current events were carried to the streets by newsboys who hawked newspapers by shouting out the most sensational headlines of the day. From the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth century, these “newsies” were the primary distributors of newspapers to the general public.

Streets have, historically, provided forums for political discourse and even confrontations involving varying degrees of violence—including the taking up arms. Since the French Revolution, the streets have played a role in the downfall of authority. Not that revolutionaries or dedicated demonstrators were the only ones to use the streets as a public arena, so did those in power: martial might on parade can draw the common folk together in shared patriotic pride or frighten a regime’s foes.

In current usage, “street” can have dichotomous meanings.

The Street, in the U.S., is used to allude to the financial and securities industry of the America. (From Wall Street, the eight-block stretch of Lower Manhattan that has been a hub for commerce and trade since the late eighteenth century.) The Street belongs to the wealthy.

However, beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, being on/in the street has meant being homeless. Since 1967, and probably before, street people has meant those who are poor, often homeless, who live in urban environments. The street is a place of last resort for with no wealth.

On one hand, the street is a source of style, chic, hipness: the perspective and creations of the urban young who are seen as constituting a fashionable, trend-setting subculture.

On the other, the streets can be viewed as a disadvantaged area of a city; an environment of poverty, dereliction, violence, and crime so pervasive that an oppositional culture—with values often intentionally antithetical to those of mainstream society—has evolved.

I suppose I could have simply said: street has many meanings; it can be an attitude as well as a location. But, then again, I could have gone on and on…

This score of stories all involve magic and streets in one way or another. They vary from the lighthearted to the somber, from the near realistic to the exotically fantastic, from the poetic to the vernacular. The incredible imaginations of the authors included have been inspired by hard-boiled detectives, genius loci, visual art, Scots and other folklore, the vicissitudes of Hollywood, the Holocaust, high adventure, noir, epic fantasy, nightlife, mysteries, runaway kids, the mythic, technology, human and inhuman nature, dreams, nightmares, and more. Some stories are fairly lengthy, others quite short, most somewhere in between.

There also seems to be a disproportionate number of bars and taverns in these twenty tales. I suppose streets have to lead somewhere.

I truly hope you enjoy this anthology. It has been fun finding the magicks and mapping the streets.

Paula Guran

Tu Bishvat 15 Shevat 5776