An Interview by Jennifer Konieczny

An Interview by Jennifer Konieczny

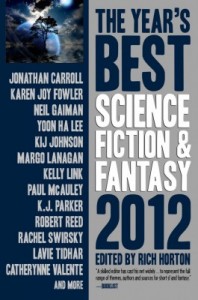

“The Adakian Eagle” by Bradley Denton will be appearing in Prime’s forthcoming Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy: 2012 edited by Rich Horton. Pre-order here!

What inspired your story “The Adakian Eagle”?

When George R.R. Martin emailed to ask if I’d be interested in writing a “paranormal detective story” for an anthology that he and Gardner Dozois were putting together, I immediately knew the story I wanted to write. I had just been reading and re-reading work by and about Dashiell Hammett (the “father” of noir mystery fiction), and I was intrigued by the life Hammett had led in the years after writing his iconic novels and stories–first as a middle-aged soldier in World War II, and then as a blacklisted author during the anti-Communist witch hunts of the 1950s.

So, given the fact that Hammett had served part of his wartime duty in a very strange and magical place–the Aleutian Islands–“The Adakian Eagle” was the only story I could write!

The protagonist notes, “And meeting Pop was how I wound up seeing the future. Trust me when I tell you that you don’t want to do that. Especially if the future you see isn’t even your own. Because then there’s not a goddamn thing you can do to change it.” If the opportunity presented itself, would you look into the future? Do you think your reaction to the future would be more like the Private’s or more like Pop’s?

Planning for the future is a good thing . . . but seeing every important detail of one’s own personal future life would be (in my opinion) awful. That would be the ultimate spoiler, wouldn’t it? We all see ourselves as the protagonists of our own stories–and nobody likes to be told the end of a story while the story’s in progress!

In that regard, I share the Private’s opinion. But if I did happen to see future events in the sort of detail that Pop does in “The Adakian Eagle,” I hope I would respond with the same kind of stoicism that he displays. (But I think Pop might have more strength of character than I do.)

Pop comments on the cartoonist’s lost cartoon, “It wasn’t his best work. I suspect he’ll do a better one now. Unfair losses can be inspirational.” How do you usually find inspiration? What’s your revision process like?

For me, “inspiration” happens whenever the things I’ve been thinking about anyway meet the opportunity to tell a story. That’s certainly what happened in the case of “The Adakian Eagle.”

I wasn’t thinking of writing a story about Dashiell Hammett while I was reading his books or biographies. I was just reading them because I was curious about him. But the more I read by and about Hammett, the more I realized that he had actually led several different (and extraordinary) lives in his 66 years. And he had suffered some “unfair losses” himself.

So when George and Gardner invited me to submit a tale to Down These Strange Streets, the story I would write for them had already been brewing in my skull. I just didn’t know it until they presented me with the opportunity.

My revision process can vary from story to story. Usually, I write an outline followed by an “everything including the kitchen sink” first draft. Successive drafts (usually three or four) then become a process of cutting out everything that doesn’t really need to be in the story.

But the road from idea to story isn’t always a straight line–and in the case of “The Adakian Eagle,” I took some unexpected hairpin turns. For example, I almost never workshop a story with another writer while the first draft is in progress . . . but in this case, I did. I showed early manuscript pages to my fellow Austin author Caroline Spector, and it was through my discussions with Caroline that I realized some of the twists and turns the mystery would have to take.

Perhaps also as a result of those discussions, the story then took its final form in just two drafts–with only a few hundred words of difference between them. That was a surprise!

Pop turns out to be Dashiell Hammett, author of The Maltese Falcon and The Thin Man. You’ve also written other historic personages, like Samuel Clemens in your story “The Territory.” How does writing a historical character differ from writing an original character? Do you have advice for writers who might want to incorporate historical figures into their work?

It’s much trickier to do a good job with a fictional portrayal of a real historical person as opposed to an original creation . . . and I’ve promised myself that I’ll never do it unless I’m convinced it’s the only way to tell the story I need to tell.

Even though the events of such a story are fictional, you have to be as true to the real person as possible. And that means research. In the case of “The Adakian Eagle,” I read three different biographies of Dashiell Hammett, as well as several of his novels and stories (including, of course, The Maltese Falcon). I also read Hammett’s wartime pamphlet The Battle of the Aleutians and some of the letters he wrote while stationed on Adak. In addition, I did a lot of online searches for photos, films, and articles about the Aleutian campaign.

So, what’s my advice for fiction writers who want to use historical figures? Whenever possible, tell the truth. Know what really happened, and incorporate those facts into your tale. For example, Sam Clemens’ younger brother really did die from injuries suffered in a steamboat explosion, and Clemens really did join a Confederate militia at the outset of the Civil War. Dashiell Hammett really did edit the camp newspaper on Adak, and he really did have black soldiers on his newspaper staff at a time when the Army was deeply segregated. Incorporating truths like those into your story not only lends verisimilitude, but also gives you, as an author, some strong clues about how such characters might really react in your fictional confrontations and conflicts.

I hope I was successful in that effort in “The Adakian Eagle.” And I hope that my story has been true not only to the legacy of Dashiell Hammett, but to the magic of the Aleutian Islands . . . and to all of the soldiers who served there almost seventy years ago.